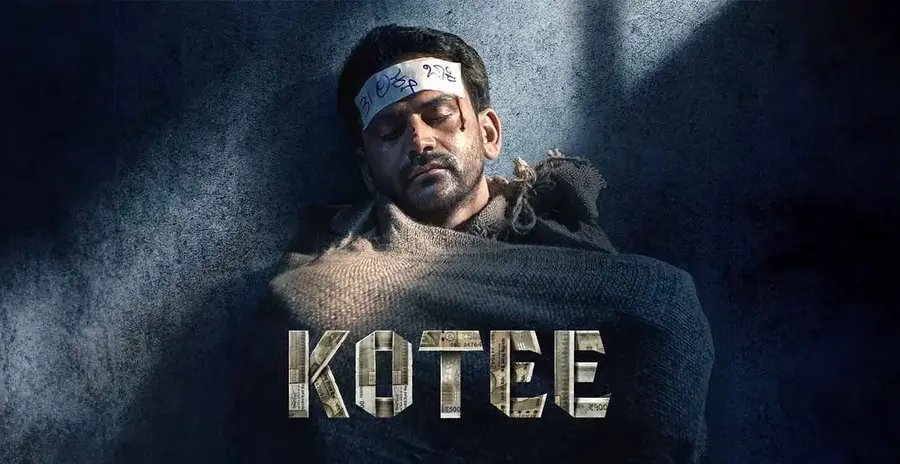

Kotee (Dhananjaya) is a mover. He helps people shift homes, and when he is not doing this, he is a cab driver. In this job, he says, he is moving people instead of things. It’s a nice line, and Param’s film is filled with lines like these. Here’s another! Kotee is a good man. He is so good that he has not even taken the bar of soap from a hotel that everyone takes when they check out. Early on, he beats up someone for cheating, and the man asks Kotee to stop acting like a saint. Everyone is corrupt, the man says, and gets to the punch: “When everyone is naked, the one who is clothed should feel ashamed.” Kotee lives with his mother, brother, and sister, and he wants to raise their standard of living. The amount he sets as a target is one crore. But can someone as sincere as Kotee earn this amount, without cheating or killing or stealing? After setting out this crux, the film takes its time getting to the issue – and at least in the first half, this is a good thing. We are immersed in the world of Kotee, and Dhananjaya creates an extremely convincing, extremely likeable man.

Good men are often boring on screen. As the saying goes, Ravana is more dramatic than Rama. But along with Dhananjaya’s performance, Param’s writing ensures that Kotee’s goodness is brought out in interesting ways. This is not the simple kind of goodness like, say, helping a blind person cross the street, or sharing a meal with a beggar. In Janatha City, the film’s location, life is more complex, and it’s harder to be a good man. To a bad man, Kotee says, “I have never asked you to stop doing bad things. You don’t ask me to start doing them.” This bad man, the villain of the story, is Dinoo Saavkar. (He’s played with creepy menace by Ramesh Indira).) He owns a theatre, which is the hub for all his illegal activities. Kotee borrows money from him, but he prefers to pay back the instalments (with inflated interest rates) rather than get rid of the loan at one shot by doing some shady work that Dinoo Saavkar wants him to do.

The subtext of the film, in other words, is how difficult it is to stick to your principles in a world where… even the heroine is a kleptomaniac. Yes, Navami (Moksha Kushal) is actually seeing a therapist to solve this issue. Can you still hold on to your goodness when your new car is stolen and your family is attacked and you are slapped for breaking something while moving (and it’s actually your co-worker who broke the thing)? How long before Kotee decides that enough is enough, and that he’d rather do whatever Dinoo Saavkar wants him to do? This dilemma, I feel, should have been the interval point, but we get to it only around the two-hour mark. The early portions of the film are endearingly old-fashioned. The narration is linear. The relationship between Kotee and his family is depicted with much love. Navami’s desire to dance in a tiger costume during the festival of Mahanavami is neatly tied to a parallel storyline about thieves who wear tiger costumes. But after a while, the leisurely approach in this two-hour-fifty-minute film begins to feel counterproductive.

There is no urgency in the second half, and the question of whether Kotee will do what Dinoo Saavkar wants him to do loses a lot of its suspense. This is not to say that the film should have been edited down to a shorter running time. The point is that even the most leisurely of narratives needs to get to its crux, the thing that sets the plot in motion and makes us worry about the plight of the protagonist. The other issue with the film is that the Navami track just does not work. Kotee and his family and Dinoo Saavkar are written so well, but when it comes to the heroine, all we get is a bunch of cliches. The “cuteness” in her portions with Kotee look artificial when compared to, say, the melodramatic rootedness of Kotee’s moments with his mother and brother and sister.